From Retired Stories of My Dad, CAPT John B. Ferriter, US Navy by Capt. Edward C. (Ted) Ferriter, USN (Ret.)

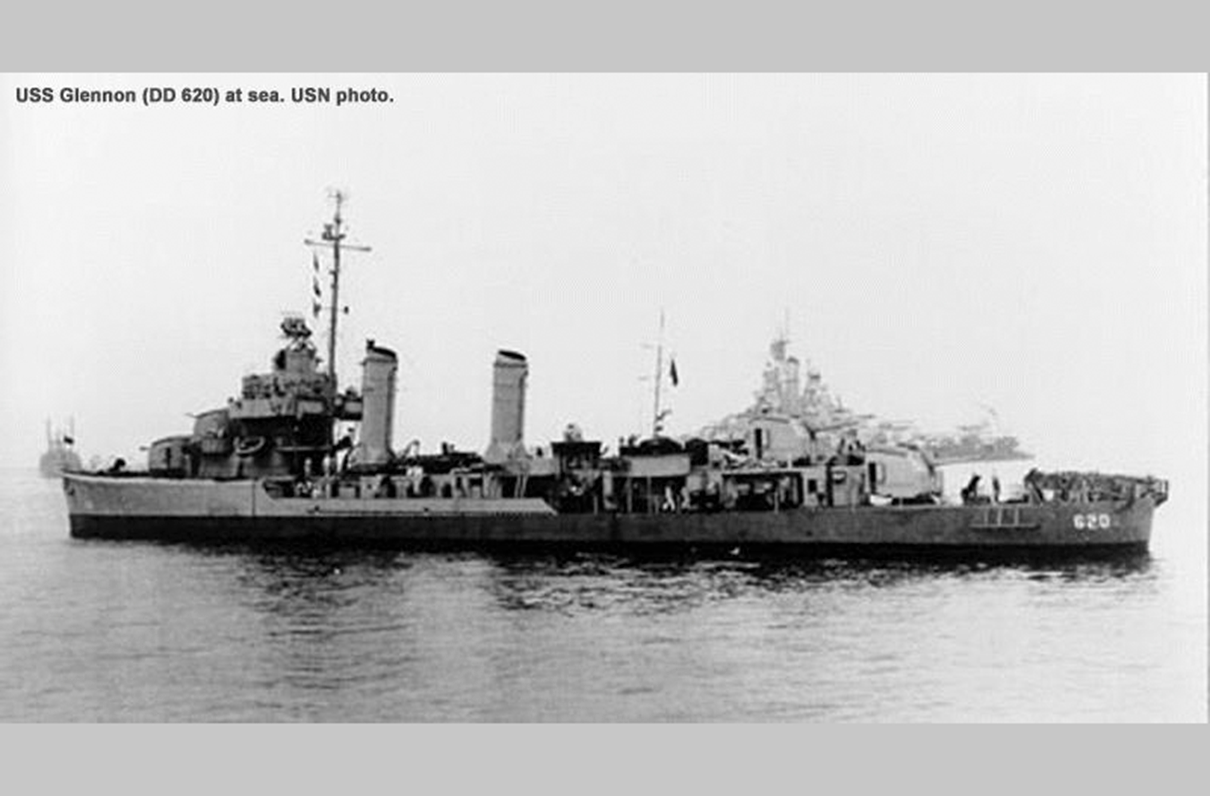

Cmdr. Charles E. Robison, USN, Retired, made an hour long video record of the two-year life of the USS Glennon, DD-620. The video was made in May 1990, almost fifty years after the sinking of the ship. Cmdr. Robison took the pictures as an Ensign from 1942 to 1944, with his new “high technology”, wind-up camera. It is an amazing story, especially for those relatives of the Glennon’s crew. There are pictures of my Dad, then Lt. Cmdr. John Ferriter, that I had never seen before: playing softball, standing watch, and leading the evacuation of the sinking ship. The video includes histories of ports of call, descriptions of action against the enemy, and the final dispersion of the surviving crew. This record follows the narration of Cmdr. Robison’s video.

The USS Glennon was launched August 18, 1942 in Carney, NJ. It was then towed to Brooklyn for outfitting. Even before its final Shakedown Cruise, the Glennon was assigned to escort a convoy to Galveston, TX in September of 1942. There are pictures of my Dad, the XO, playing softball in Texas with the crew, getting a few hits and running bases. CDR Robison said, “There’s Johnny Ferriter,” with just a bit of admiration and camaraderie in his voice.

After the Shakedown Cruise, the ship sailed for Casa Blanca, Morocco, and Dakar, Capital of French West Africa. The squadron was sent to Dakar to monitor a group of five French Navy ships that had escaped capture by the Germans. Those French ships never moved. Later, in the spring of 1943, the Glennon was part of an enormous convoy of troop transports heading to Sicily. Cmdr. Robison describes the formation of over a hundred ships and the destroyer’s role escorting the formation. There is footage of Dad with the control of the ship during a difficult maneuver alongside to transfer material from one ship to the other.

In the summer of 1943 the squadron, along with hundreds of other ships, staged in Algiers and prepared for the invasion of Sicily. They provided shore bombardment off the town of Gala, Sicily. A sister ship, the USS Maddox, operating 4 or 5 miles west of the Glennon, just disappeared. Nothing of the ship was recovered. It was suspected the ship hit a mine.

At Normandy, in June 1944, the squadron was assigned a naval gunfire support area two miles from the UTAH Beach landing site. Cmdr. Robison said, “There were mines going off all over the place.” At 4:00 a.m. on D+1 the Glennon hit a mine. The USS Rich came in to assist and take on casualties. The skipper of the Glennon told the Rich his ship was not in danger of sinking and they should stand off and watch out for mines. Almost immediately the USS Rich hit a mine, breaking the ship in two. The forward half then hit another mine. A third mine sent the Rich to the bottom. There were very few survivors.

The Glennon was now “anchored” by its stern in relatively shallow water, approximately 30 feet deep. The Commanding Officer’s, record of the event notes: “The USS Glennon had been grounded astern by a German mine detonating under the port quarter partially breaking the after section off.” According to the Commanding Officer, Dad remained on board with a small crew of “one other officer and eight men to maintain power to keep pumps in operation which would prevent further flooding and possible sinking of the ship.” The Glennon’s stern remained attached to the forward part of the ship by the propeller shaft. Attempts to cut the forward part of the ship free were made, however no divers could enter the water because concussions from nearby exploding mines would kill them. Cmdr. Robison, mentioned that on D+2 or 3 the Germans found their range and the ship began to take heavy damage. The Commanding Officer's record continued: “The ship was within range of German batteries located at Quineville, France, which had previously shelled the ship.” Nearby PT boats laid down smoke for concealment, and Allied aircraft attempted to suppress German gunfire.

Cmdr. Robison had many pictures of the damaged Glennon and the crew working feverishly to save her. Finally, an order from higher authority came to abandon ship. The last two members of the crew to leave the ship were Dad and the skipper. After boarding the ship’s motor whaleboat, the remaining crew took a final turn around the Glennon for one last look at the ship that had been home for two years. The crew was ordered to a nearby LST taking wounded and other survivors back to England.

The crew of the Glennon later moved to Scotland to await orders to other ships or commands needed by the Navy. Most of the crew returned to the US via the Queen Elizabeth (I), transiting the Atlantic at 30 knots with no escort. CDR Robison reported to the USS Owen in the Pacific, Dad reported to the USS Knight (DD-633) as Commanding Officer.

In every port the ship visited, Ensign Robison took pictures of the Glennon’s crew on liberty and scenes of the ports: charcoal burners mounted on cars and buses in Africa that used carbon monoxide for power; native women thrashing grain with long poles in Dakar; sailors on horseback in Bermuda; US Navy PBYs at anchor in Gibraltar; liberty parties in Algiers. Later, when assigned to a different ship in the Pacific, Ensign Robison took pictures of officers and crew of the USS Owen walking through Hiroshima and Nagasaki a scant month after the bombing.

The basic make up of a squadron of destroyers, then and today, consists of eight ships, the specific size of the squadron depending on the mission tasked and the availability of resources. Cmdr. Robison never mentions the actual name/number of the squadron (such as Dad’s DESRON 20) just that there were eight ships in the squadron, and he listed their names. To me the single most surprising part of the entire narration is that six of the eight ships originally assigned to the squadron were either sunk or heavily damaged during the war. Five ships were lost in combat. This is an indication of the constant danger these small but powerful, fast and deadly ships faced throughout WWII.

Those six destroyers were:

- USS Maddox – Lost at sea during the invasion of Sicily;

- USS Murphy – Cut in two by a large transport ship during convoy operations, returned to service after extensive repairs;

- USS Nelson – Hit by a U-Boat, out of action for the Normandy invasion;

- USS Rich – Hit three mines at Normandy, broke apart and sank;

- USS Corry – Sank at Normandy,

- USS Glennon – Sank at Normandy.

Cmdr. Robison visited Normandy in 1987 and found memorial plaques to each of the three destroyers from the squadron that sank off UTAH Beach in June 1944: USS Glennon, USS Rich, and USS Corry.

Capt. Ted Ferriter, USN (Ret) served over 30 years in Naval Aviation, primarily in the P-3/Maritime Patrol community. He is retired and lives in rural Virginia.